“The tradition of cooking carlins is relatively unheard of today. But we still mark the occasion at Beamish, usually by cooking peas, seasoned with either salt and vinegar or sugar! See carlin pea displays at Pockerley Old Hall and The 1900s Pit Village.”

Beamish Museum website

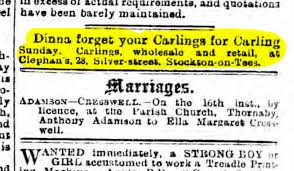

The fifth Sunday in Lent and is known as Carlin Sunday due to its association with Carlin peas, one of the few surviving localised dishes perhaps in England – I had never heard of them until I had visited the north and read more in books on folk customs – but despite what Beamish says above is still enacted and the peas can be seen for sale in northern soups and elsewhere. In the North a saying; developed to help people remember what days were what being derived from the psalms and hymns and names of the Sundays in Lent:

“Tid, Mid, Miseray, Carlin, Palm, Pace-Egg Day”

Tid was the second Sunday when Ye Deum Laudamus was sung, Mid was third Sunday when the Mi Deus Hymn was sung, Miseray – the fourth Sunday, was when the Misere Mei Psalmwould be chanted and then Carlin, the fifth Sunday, Palm the sixth and final and Pace Egg was Easter Sunday. As the communities became separated from the Catholic doctrine it would seem only the last three would be remembered.

Give peas a chance!

So what are Carlin peas? They are dried maple peas or pigeon peas often fed to bord and used for fish bait, but somehow became a Lenten staple. The were usually soaked in salt water overnight on Friday, then on Saturday boiled in bacon fat enabling them to be eaten cold or hot on the Sunday, often being served with a sprinkling of salt and pepper, vinegar or rum.

Two peas in a pod

So why the North only? Well, there are two origins said to why the peas were restricted to the North-east as related in Chris Lloyd in his excellent 2021 Northern Echo article “Why the North-East traditionally spends today eating dried pigeon peas.:

“This tradition may have started in 1327 when Robert the Bruce and his Scots were besieging Newcastle. The starving Novacastrians were saved on Palm Sunday when a shipload of dried peas – perhaps sailed by Captain Karlin – arrived from Norway. Fortified by the carlins, the defenders fought off the Scots who went and attacked Durham instead.

Or it may have started during the Civil War in 1644 when, from February 3 to October 27, another army of Scots besieged the Royalist forces in Newcastle. This time, Captain Karlin arrived with a boatload of peas from France to save the day”

Versions of this later story have the ship of peas wrecked or stranded at Southshields a fortnight before Easter Day, which was also in time of famine and the peas washed ashore and were eaten, the salt adding to the flavour, which is still recommended to eating it. And equally say the shop came from Canada. Despite being a North -eastern tradition it soon spread to Yorkshire and Lancashire – my first experience was at a Good Friday fair just south of Manchester..

In the 20th Century, the tradition began to die out, although it seems to have clung on in pubs. With all pubs now closed, perhaps the pandemic will kill off a North-East tradition that may be 700 years old and could have been started by Captain Karlin.

A correspondent of Notes & Queries (1st S. vol. iii. 449) tells us that on the north-east coast of England, where the custom of frying dry peas on this day is attended with much augury, some ascribe its origin to the loss of a ship freighted with peas on the coast of Northumberland. Carling is the foundation beam of a ship, or the beam on the keel.

So there is another explanation of the name. Yet another suggestion is made by Brand in his 1849 Popular. Antiquities:

“In the Roman Calendar, I find it observed on this day, that a dole is made of soft beans. I can hardly entertain a doubt but that our custom is derived from hence. It was usual among the Romanists to give away beans in the doles at funerals; it was also a rite in the funeral ceremonies of heathen Rome. Why we have substituted peas I know not, unless it was because they are a pulse somewhat fitter to be eaten at this season of the year.” Having observed from Erasmus that Plutarch held pulse (legumina) to be of the highest efficacy in invocation of the Manes, he adds: “Ridiculous and absurd as these superstitions may appear, it is quite certain that Carlings deduce their origin from thence.”

This explanation, however, is by no means regarded as satisfactory.

Pease offering

Chris Lloyd (2021) states:

“I remember when I lived in the Stokesley area, neighbours used to mention Carlin Sunday and it was something to do with eating peas on that day. I wondered if you would be able to find out more about it, please?”

He also states that they were commonly sold at fairgrounds and mobile food counters, being eaten with salt and vinegar as I had. Lloyd (2021) notes that:

“At fairgrounds, they were traditionally served in white porcelain mugs and eaten with a spoon. In more recent years, they have been served in thick white disposable cups”

And that in:

“ world famous Bury Market and in Preston, parched peas are sold ready-cooked and served in brown-paper bags or in plastic tubs.”

He also claims that:

“Consumption is limited to certain areas within the historical boundaries of Lancashire, notably Oldham, Wigan, Bury, Rochdale, Prestob, Stalybridge, Leigh, Atherton, Tyldesley and Bolton.“

However it may have had a wider distribution. Thistleton-Dwyer’s 1836 Popular customs states:

“On this day, in the northern counties, and in Scotland, a custom obtains of eating Carlings, which are grey peas, steeped all night in water, and fried the next day with butter.”

It is indeed remembered in Ritson’s Scottish songs:

“There’ll be all the lads and lassies. Set down in the midst of the ha’, With sybows, and ryfarts, and carlings, That are bath sodden and raw.”

Whatever the truth despite a decline and apparent disappearance in the early 20th century, carlin peas are now again sold in pubs and in food stores and carlin Sunday continues.