“Such elaborate junketing may sound a little odd to anyone unconnected with All Souls . . . But presumably, if Homer may be excused an occasional nod, a Fellow of All Souls may be allowed, once in a hundred years, to play the fool.”

Account from Cosmo Lang’s Biography

Back in 2001 I was invited to see a strange spectacle which by its rarity and unusual description I honestly didn’t believe actually existed, All Soul’s College Hunting the Mallard. Sadly in the end I could not go and missing out in a way cemented by desire some may say obsession to catalogue our curious and colourful customs. Why? Well because the Hunting of the Mallard is the rarest of beasts, as rare as the said Mallard, as it is only done every 100 years.

Interestingly Thistleton-Dyer in his excellent Popular customs past and present 1876 appears unaware of the 100 year cycle recording:

“This day was formerly celebrated in All Souls College, Oxford, in commemoration of the discovery of a very large mallard or drake in a drain, when digging for the foundation of the college ; and though this observance no longer exists, yet on one of the college ” gaudies ” there is sung in memory of the occurrence a very old song called ‘ The swapping, swapping mallard.”

Ducking and diving

As noted above the Mallard has a strong association with this venerable Oxford college; it is their mascot and can be seen on various objects around the college. But how did it all start? 1437 is the date given when during the digging of the college’s foundations the college’s founder Archbishop of Canterbury, Henry Clichele, was indecisive of where he should build his college. But during a dream he was told that:

“…a schwoppinge mallarde imprisoned in the sinke or sewere, wele fattened and almost bosten. Sure token of the thrivaunce of his future college”

The location in the dream was next to the church and upon digging where he was directed and could hear in a hole: “horrid strugglinges and flutteringes” reaching in he pulled a duck describe as the size of “a bustarde or an ostridge.” This was a the sign and as the bird flew away the academics who were to become the Fellows of All Souls chased it, caught and then of course ate it! And so immortalised the bird in the college’s history.

When the custom started is unclear but an account by Archbishop Abbott in 1632 is the earliest recording:

“civil men should never so far forget themselves under pretence of a foolish mallard as to do things barbarously unbecoming.”

It may have been thoughts like this which resulted it in being a 100 year cycle!

Yes Mall’ord

On the night of January 14, 2001, some of Oxford’s most learned fellows could be seen marching around All Souls College behind a wooden duck held aloft on a pole. They were engaged in the bizarre ritual of hunting the mallard that occurs once every 100 years at the College. I was up at Oxford at the time, and one of my tutors was present and so I got the eye-witness account of the matter.

After a commemorative feast the fellows paraded around the College with flaming torches, singing the Mallard Song and led by “Lord Mallard” carried in a sedan chair. They were in search of a legendary mallard that supposedly flew out of the foundations of the college when it was being built.

And so, during the hunt the Lord Mallard is preceded by a man bearing a pole to which a mallard is tied. Originally it was a live bird, by 1901 it had become a dead bird, and by 2001 it was a bird carved from wood. The last mallard ceremony was in 2001 and the next will be held in 2101.

How many hunting the mallards there officially have been is unclear – one presumes six – as little is recorded. The only one to have been documented before the 2001 one was the 1901 custom. The Mallard Lord being Cosmo Gordon Lang, who recalled via J G Lockhart, his biographer:

“I was carried in a chair by four stalwart Fellows – Wilbrahim [First Church Estates Commissioner], Gwyer [later Chief Justice of India], Steel-Maitland [later Minister of Labour] and Fossie Cunliffe – for nearly two hours after midnight round the quadrangles and roofs of the College, with a dead mallard borne in front on a long pole (which I still possess) singing the Mallard Song all the time, preceded by the seniors and followed by the juniors, all of them carrying staves and torches, a scene unimaginable in any place in the world except Oxford, or there in any society except All Souls.”

The account related that in 1901 that:

“The whole strange ceremony had been kept secret; only late workers in the night can have heard the unusual sound, though it is said that Provost McGrath of Queen’s muttered in his sleep, ‘I must send the Torpid down for this noise.”

At the end of the event Lang notes that the dead mallard was thrown on a bonfire to which Lang noted:

“some of the junior fellows could not be restrained from eating portions of its charred flesh”.

Its all quackers!

As the procession hunted the duck the procession would sing the Mallard Song:

“The Griffine, Bustard, Turkey & Capon

Lett other hungry Mortalls gape on

And on theire bones with Stomacks fall hard,

But lett All Souls’ Men have ye Mallard.

CHORUS:

Hough the bloud of King Edward,

By ye bloud of King Edward,

It was a swapping, swapping mallard!

Some storys strange are told I trow

By Baker Holinshead and Stow

Of Cocks & Bulls, & other queire things

That happen’d in ye Reignes of theire Kings.

CHORUS

The Romans once admir’d a gander

More than they did theire best Commander,

Because hee saved, if some don’t foolle us,

The place named from ye Scull of Tolus

CHORUS

The Poets fain’d Jove turn’d a Swan,

But lett them prove it if they can.

To mak’t appeare it’s not att all hard:

Hee was a swapping, swapping mallard.

CHORUS

Hee was swapping all from bill to eye,

Hee was swapping all from wing to thigh;

His swapping tool of generation

Oute swapped all ye wingged Nation.

CHORUS

Then lett us drink and dance a Galliard

in ye Remembrance of ye Mallard,

And as ye Mallard doth in Poole,

Let’s dabble, dive & duck in Boule.

CHORUS”

The song is not restricted to the Mallard and is song at events such as the Gaudy held annually.

Duck soup

In 1801 it was said that a live mallard was chased around, by 1901 it was a dead one on a pole and by 2001:

“There will be a wooden mallard duck carried at the head of the procession on a pole.”

The History Girls blogsite accounted that in 2001 Dr Martin Litchfield West was the Mallard Lord it reported:

“Behind Dr West, fortified by the Mallard Feast and dressed in black tie and gowns, marched the other fellows of the college. Among those expected to participate were William Waldegrave and John Redwood, members of the last Conservative Cabinet, and Lord Neill of Bladen, former chairman of the committee for standards in public life and once warden of All Souls. All fellows taking part in the procession are expected to give full voice to the Mallard Song. …There will be 118 people, all fellows or past fellows, carrying torches. We shall go around the college and up the front tower and back again. We will then join the college servants for a lot of drinking and there will be a fireworks display.”

An account of the custom first hand related to the blogger of the excellent History Girls blogsite notes:

“My tutor gave us the insider’s view of the Great Mallard Chase of 2001. She and the other Fellows partook of a 14 course dinner in the medieval Codrington Library, accompanied by superb wines (All Souls has the best cellar in the country – better than Buckingham Palace). I have reprinted the menu from 1901 below. Dr Martin Litchfield West as the Lord Mallard, and the Fellows sang, much as they have done for hundreds of years, the Mallard Song. The Victorians disapproved of the reference in the song to the Mallard’s “swapping tool of Generation”, mightier than any other in “ye winged Nation” (of birds) and dropped this verse from the song. It was restored in the 2001 ceremony, when the Fellows sat down to the Mallard Centennial Dinner, which did include a duck. When everyone was in an excess of good spirits, four of the younger fellows hoisted the Lord Mallard up in his special sedan chair (the same one used in 1901 – but we’re not sure if it was also used in 1801) and they chased a wooden mallard duck around the quad. In the days before Animal Rights (a very serious consideration in Oxford, given letter bombs to scientists and sabotage of laboratories), they chased a real duck. But this century, for the first time, a fake duck had to do. So, with the Lord Mallard hoisted high in his sedan chair the whole congregation of fellows chased this wood duck around the quadrangle bellowing out the Mallard Song. Now, given that he was not expending any energy and was the centre of attention, the Lord Mallard was anxious to repeat the experience. “Again, again” he cried, and he was carried around the quadrangle again, and then for a third time at his excited urging. But, when he said “Again”, wanting a fourth perambulation, the poor sedan carriers rebelled and dumped him on the ground. Then there were wonderful fireworks, including fireworks in the shape of a mallard. “

Sad to have missed it and not a single photo…ah well here’s to 2101!!

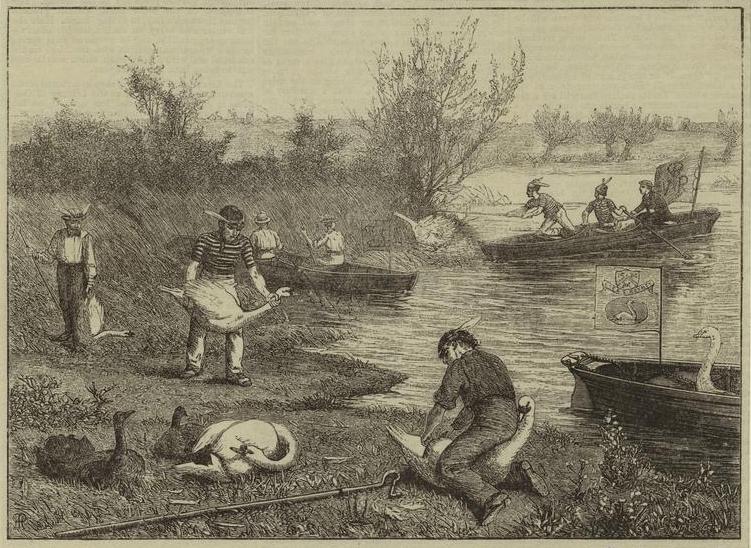

The delightful mute swan, gliding majestically down the river, its pure white plumage shining in the summer, has always been thought to be a Royal bird. The monarch owning all birds but in the past ownership was granted to certain groups and since the medieval times to two livery companies – The Vintners and Dyers. These two companies have what is called the royalty of swans. Margaret Brenthall in her 1975 Old Companies and ceremonies of Britain:

The delightful mute swan, gliding majestically down the river, its pure white plumage shining in the summer, has always been thought to be a Royal bird. The monarch owning all birds but in the past ownership was granted to certain groups and since the medieval times to two livery companies – The Vintners and Dyers. These two companies have what is called the royalty of swans. Margaret Brenthall in her 1975 Old Companies and ceremonies of Britain: